What can we say to parents who are baffled by the fact that their child has been receiving special education for some time, and yet, their child still cannot read with any degree of consistency?

On the surface, it looks like everything that can be done is being done, and many parents have become resigned to the idea that their child will always be on the outside looking in with regard to knowing how to unlock the hidden mysteries of the English language.

However, this should not be the case. “Scientists now estimate that fully 95 percent of all children can be taught to read. Yet, in spite of all our knowledge, statistics reveal an alarming prevalence of struggling and poor readers that is not limited to any one segment of society.”(1)

Why? Because just as the title of this prolific article states Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science. Teaching reading is a job for an expert; and furthermore, teaching a disabled child to read requires even greater precision, skill, and expertise. Additionally, one particular approach, no matter how good it is, cannot be universally applied.

As a Literacy and Language Specialist, I continue to be amazed at the complexity and arbitrary nature of our language. Why do certain consonants make different sounds based on their proximity to a vowel? Why does the consonant y function as a consonant and as a vowel? Why can’t the phonics rules be applied to all words? How do we explain to children that many of our words don’t follow the rules, and can’t be sounded out? These are words such as the, was, and what.

Teaching reading is rocket science because learning to read and write with ease and fluency is as complex as learning to decipher a scientific formula. Acquiring the necessary skills requires a deep understanding of the structure of language and the ability to apply and process it fluently. For a child with a learning disability, this process can appear to be insurmountable.

The parents of these incredibly bright children often feel like they have failed their children in the most basic way. They have taken the suggestions, helped with homework, waited patiently, and the stark reality is that with each year that passes, the gap between their child’s ability to read and write as compared to peers is widening not closing.

Why is it that parents are struggling to reconcile the idea that they are living the experience of parenting a child who can’t read, but their child’s progress report states that s/he is progressing at school?

Many times a child will receive a progress report based on the goals of his/her IEP that states, “Bill is making effective progress toward his/her reading goal as measured by the following objectives…” The objectives will be listed and progress will be documented with percentages or number of trials.

This is valuable progress measured by school wide assessments, such as the Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA) or The Teacher’s College Reading Project. These assessments require a child to look at a series of pictures, make predictions, and as the grade levels increase, read text.

So, if your child began first grade at a DRA of 3 or a Guided Reading Level C and ended the year at a DRA Level 10 or a Guided Reading Level F, it does represent progress, however; the most important thing to understand is that these reading passages contain pictures and the examiner gives the child the background of the story so a child may have learned to read the words by memorization and/or has used the picture cues to predict the words.

Using picture cues and context clues are excellent strategies, but they are NOT effective for teaching a child to decode a word, which requires a student to sound out a word based on its sound/symbol correspondence.

Teaching a child to read requires that s/he knows:

- The difference between letters and sounds

- All letter names and corresponding sounds

- How to manipulate sounds

- How to identify and produce rhymes

- What a rhyme is

- What a rhyme is not

- What alliteration is and how to create a sentence with alliteration

- How to identify the beginning, middle, and ending sounds of words

- What is a paragraph, sentence, word, syllable, and sound and why and how are they different?

- How to blend and segment sounds and syllables

There are many more, but the acquisition of these skills begins to develop cognitive flexibility around language processing in an individual, and this is necessary before any meaningful learning can occur.

What we are really doing as reading teachers is teaching children to think analytically about the English language. It is like teaching them how to examine an algebra equation or learn the properties of matter. Without a rich and thorough understanding of the underlying structural principles, it amounts to a guessing game.

If your child is showing improvement according to data collected in the academic setting, but s/he is not reading at home, is not spelling words correctly in unstructured activities, such as writing down their chores or writing a letter to Santa Claus, then s/he has not mastered the fundamental skills necessary to unlock the language and become a reader.

However, once your child begins to understand the mystery of the English language in its entirety, it becomes a puzzle that CAN BE SOLVED! When this begins to happen its manifestation is unmistakable. There are very specific signs that you can look for as a parent.

You will begin to notice your child reading signs in the car, supermarket, and at the movies. Children start to sound out the names of their snacks, such as cupcake. Then, they take it a step further and inform Mom and Dad that cupcake is a compound word made of a closed and vowel-consonant-silent e syllable. Younger children begin to attach meaning to spatial concepts, such as time. They will know their birth month and the corresponding season.

Children who were not reading basic text, begin to read! Kids start talking to their parents about basic things like fruit and begin to rattle off a series of words that rhyme with that fruit along with the rhyming sound. For example, “Lime, dime, time, the rhyming sound is ime.”

They become language experts and begin to teach their parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, siblings, and anyone who will listen that letters are very different from sounds, that a person’s name like Shane has five letters, but only three sounds because sh is a digraph which has two letters that make only one sound, and furthermore, it is a vowel-consonant-e syllable so the letter e is silent.

Five and six year old children begin to explain to parents that the alphabet is made up of letters, but there are consonants and vowels and you can never have a word without a vowel. Then, they go on to explain that there are words that don’t follow the rules and we have to work with these words for much longer because we must store them in our brain as a picture because they can’t be sounded out. Words like the and there.

Children start sounding out words. They begin to connect subjects realizing that one of our states (Alaska) begins and ends with a schwa.

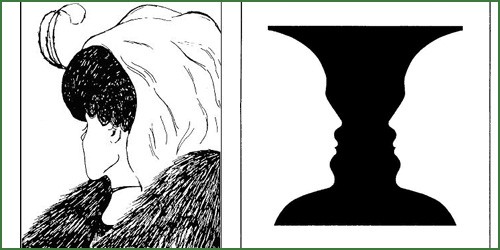

These children begin to read words and understand language everywhere they go because the world is language based. Once the puzzle is unlocked, it can never be relocked. It’s like looking at an image that portrays two images within one illustration. You can stare at it for years and never see both perspectives, but once someone teaches you what’s there, you can never un-see it. (See examples of this type of image at the top of this blog.)

Learning to read can be a frustrating experience similar to looking at these images and not being able to see both perspectives, but it’s important to remember that every child can be taught to analyze the English language at its core level. Once a child understands the fundamental speech sounds (phonemes), s/he can simultaneously be taught to map these sounds to letters (graphemes) and the unlocking process begins.

The process of teaching a student how to read can be compared to a medical model. An individual with a disability needs a highly skilled clinician, just like a patient needs a doctor. Research has provided the evidence, but just as a doctor has the skill and knowledge to know which antibiotics work on which bacteria, he does not give everyone with a bacterial infection the same dosage. He uses his knowledge and experience to treat the individual based on his/her needs. It’s the same with the clinician. To paraphrase Torgesen, the effective clinician treats the student with the precise kind of interventions, correct rigor, at the right time, and with the right intensity.

So, if your child is receiving special education and is reported by the school system to be making effective progress, but he still cannot read and write through the course of daily activities, then the correct instruction is not being designed and delivered properly.

The only thing that really matters are the results – and the results can be seen by everyone. In the medical scenario, the patient gets better and within 7-10 days it’s obvious that the antibiotic is working. In the academic scenario, the student learns to unlock the mystery of the English language and within 7-10 sessions, if not sooner, he is empowered by the fact that he can learn to read and write.

(1) American Federation of Teachers, Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science, 1999.

Jaydin Skinner says: